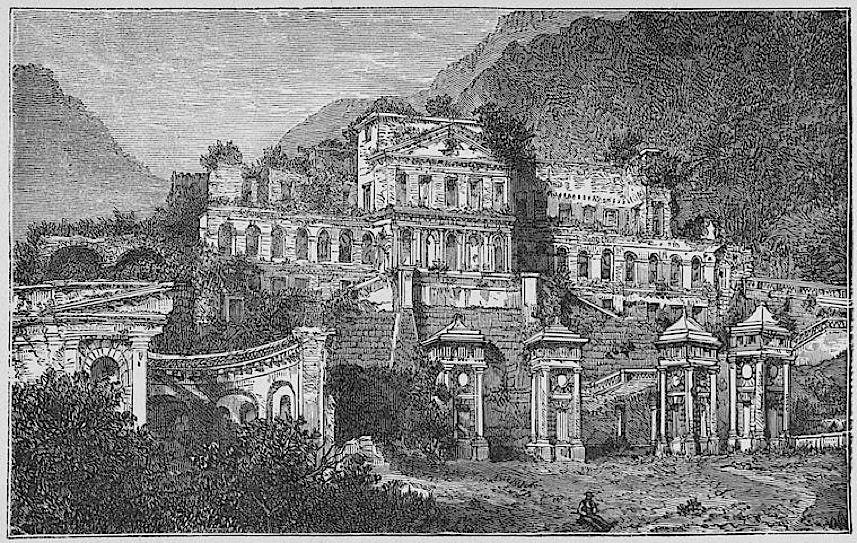

Between 1791 and 1804, enslaved people in Haiti did what was impossible. They overthrew a colonial regime, established the first free Black republic, and even built a Black Sans-Souci – complete with running water and magnificent gardens.

What makes this revolution particularly interesting is not just that it happened at all, but how it exceeded everyone's imagination – even while it was taking place. Even those enacting it couldn't fully formulate its claims in advance.

It was just too radical.1

This article explores how such moments of ‘unthinkability’ shape our future – not just historically, but today. As we face grand transformations that exceed our very capacity to imagine them, it helps to shed some light on how our frameworks for thinking about the future constrain us, and how embracing these very limitations can unlock new possibilities.

Imagination Failure

The Haitian revolution was genuinely unthinkable for everyone involved. It only became what it was in hindsight.

The colonisers couldn't think it: Their entire worldview was built on the premise that enslaved people were property, not agents of history. When confronted with organised resistance, they tried to understand it through familiar frameworks: peasant revolts, foreign manipulation, temporary unrest. Even as their system crumbled, they couldn't grasp what was happening because it challenged the very categories they used to make sense of the world.

The revolutionaries themselves couldn't fully think it: They were creating something that had no precedent, no model to follow. Even as they fought for freedom, their imagination was shaped by the very systems they were fighting against – they had rigid and brutal oppression in the own lines, eventually partly re-establishing a system of dominion and absolute power internally. They, too, were challenged with having to act beyond what they could imagine, pushing into territory that their own conceptual frameworks couldn't fully contain.

The historians couldn't think it: For generations, especially French observers struggled to document what happened, trying to fit this radical rupture into existing narratives of revolution and nation-building. But Haiti's revolution wasn't just another revolution - it was a fundamental challenge to the entire colonial world order, to basic assumptions about human capacity and political possibility. It took more than a century for us to slowly grasp the fundamental significance of that event.2

This unthinkability, this gap between what we can imagine and what might become possible, tells us something crucial about how we think about futures. It raises fundamental questions about imagination, about the limits of our own thinking, and about power.

Haiti’s revolution suggests that the most transformative changes might come not from expanding our imagination, but from its failure - from moments when reality exceeds our capacity to think it.

We’re living through many such failures today: The deep and fundamental impacts of climate change are both, genuinely beyond our collective comprehension, and already here.3 The collapse of the old Western hegemonial order of past centuries is palpable, yet no one seems to grasp whats next. Technology has now learned to simulate sentient communication,4 and while its effects are already seeping into everyday life, critics and proponents, both, can’t keep up with what that even means.

Like the Haitian revolution, these transitions aren't just surprising or unexpected - they challenge the very categories we use to make sense of the world. They are unthinkable not because we haven't thought hard enough, but because they exceed the frameworks within which we do our thinking in the first place.

How do we engage with what we can't yet think? How do we recognise when our inability to imagine something might be precisely what makes it possible? And how do we work with, rather than against, the limits of our own imagination?

Revisiting the Future

Today, futuring™️ has become a default response to uncertainty. The prominent call for ‘Better Futures’ promises to make our future debatable and designable, to help us chart our own trajectories of change – and to deal with present day challenges by transposing them into a fictional, not yet decided (and therefore not as dire!) future space. Reversely, good (critical) futurists will embrace a multi-future approach, looking for ‘option spaces’, desirable possibilities, for hope, and for paths to chart back to inform present action. Futuring has become a powerful tool for rethinking assumptions and shifting our mental 'problem space'. And personally, I find mz self clinging to those desirable futures, visions worth fighting for, that help us in orienting and strategising whats next – at least in theory.

But in practice, when working with futures, there are a few inherent shortcomings that get overlooked just too often. They have been highlighted before, to be sure.5 Yet, in current discourse and routine, I see them to be brushed over quite quickly.

So let's revisit.

1. Coherent Futures

The first problem with the call for better futures is that it implies coherence.

When we imagine futures, we can't help but make them coherent. We sketch clean lines around messy possibilities, reaching for familiar archetypes: the gleaming corporate tech-utopia, the sustainable solar-punk community, the fractured democratic landscape, and the post-apocalyptic wasteland…

As helpful (and fun!) as these are as narrative instruments, they are highly problematic for informing our design and governance choices. In this regard, they resemble clichéd user personas. Both are neat, popular, and wrong. While their value lies in simplifying reality, neither futures nor humans are as coherent as these narratives suggest. In reality, they are dissonant, patched up and conflicted. That means: they are virtually impossible for us to tell a coherent story about. Virtually impossible to fully imagine.

It’s Heisenberg’s Future: By looking too closely and making it insincere imaginaries too explicit, we inadvertently push too hard for coherence and clarity – and we risk ignoring all the dissonance, ambiguities, and chaos that truly drive change. If we don’t push at all, we might see the world but it doesn’t make sense.

2. Myopic Futures

The second problem with future imaginaries is where they end.

Futures are filter devices. They allow us to gain clarity about today's choices by de-noising what's ahead. When drawing them up, we focus on their content: the stories we want to tell, the themes and topics we want to explore, the metrics and patterns we want to see. All the rest – the noise – gets pushed out of scope, off-frame. That is their point.

That frame, however, is where it really gets interesting: What does it look like? Where do you draw it? And whats beyond?

To make it concrete: When speaking about a future of mobility, education, or health – why are we still talking about cars, schools, or hospitals? How much of our future thinking is stuck within the frames of the old? And how would we even begin to speak about these futures without those frames? What is the effect of a pandemic of the future of mobility? Could a future of health focus on community resilience or labour rights instead of hospitals? Could a future of education prioritise peer-to-peer learning or gardening over schools and tests? Or wouldn’t it all just become a big buzz-wordy blur?

On the other side of the filters we create is something we can call the unmarked state: the noise beyond our frames, a realm where distinctions, boundaries, and definitions haven’t yet been drawn. Future imaginaries are not only unrealistically consistent but also arbitrarily selective about their own scope, carrying their own blind spots and myopias. Each ends somewhere, leaving much unsaid.

Emerging approaches like critical, black, Muslim, or queer futures6 recognise this dynamic, explicitly pushing for the inclusion of those voices and perspectives that historically have been placed at the other side of that frame.

That is important and overdue – but (as many scholars in these fields point out) we can only shift, not solve, our myopias: Regardless of how much inclusion and integration we push for, there will always be another side to the stories we're telling. Our future always end somewhere. And the other side of that end tends to hold the surprises and connections we considered irrelevant before.

Michel-Rolph Trouillot7 explores how in Haiti, even the most radical, most ambitious revolutionaries could not cross that frame of their own imaginaries. They could not imagine what would come after what is now. And even after it happened, it took generations to actually process, and imagine it. Haiti’s revolution was just so outrageous that it was existing out-of-frame before, while, and even after it took place.

How so? How did it end up out there and stay there for so long?

As always, there’s a simple answer to that question:

Power.

3. Silent futures

The third problem with futures is how loud they are.

Power is what we call that capacity to push things out-of-frame. It is not external to how we make our images. It is our images, and integral to how we make them.

Not only become the out-of-frame stories particularly telling when we want to learn about ourselves. They point us to how that power takes place. Because by telling one story about the future, we silence all the others.

Trouillot sheds some light how that silencing is taking place. And, to be sure, this is a silencing of both, pasts and futures:

Silencing at the moment of creation → Power over Future Sources

Omitting original voices and perspectives on potential, desirable, or avoidable futures. (Think ‘fringe’ literature, community forums, local planning meetings, elders, marginalised groups.)Silencing at the moment of assembly → Power over Future Archives

Omitting records, documents, and memories of futures. (Think library catalogues, reading lists, curricula, algo recommendations.)Silencing at the moment of retrieval → Power over Future Narratives

Filtering out alternative interpretations of the future, differing ways of sense-making, and diverse connections. (Think social media feeds, news aggregators, search results, workplace conversation patterns.)Silencing at the moment of attributing significance → Power over Future Histories

Shifting attention, focus, or recognition away from networks of narrative that make History, both past and future. (Think academic citations, media coverage patterns, expert validation systems, institutional memory practice.)

The effect of neglecting silenced futures is that we end up in a loop of variations of the old. Not only is this boring cycle of nostalgia trapping us in our own pasts. It’s a power move that keeps all the other pasts and futures at bay – an endless Now at the expense of the New.

The eternal circle of the reproduction of the same is not based on external constraints, but on the superiority of the visible and the nameable over the never-before-seen. – Lucius Burckhardt

Embracing the Edge

That’s a simple enough diagnosis. Let’s just mess up, un-frame, un-silence our imaginaries then, and we’re good? Maybe a few new frameworks that ask just the right questions, a few more critical formats, more reflection and diversity – then we might just get there and think beyond our frames?

An image without a frame is no image at all.

To think we can just ✨imagine✨ our way out of our confined perspectives sounds great. But, ultimately is impossible. When we try to make unthinkability thinkable, we domesticate it – and when we don’t, we literally cannot think it. Trying still, we turn it into something that fits our existing categories of thought. And eventually we trick ourselves.

Mark Fisher showed us how impossible it is to try and think beyond the frame of capitalism while stuck within it8 – maybe just as impossible as it was for those Haitian revolutionaries to think within and outside of the frame of colonialism. Equally, efforts to account for centuries of racist oppression today often end up replicating the very patterns they strive to overcome – cue the romanticisation of noble ‘indigenous wisdoms’ we just have to re-discover (and then, surprise, appropriate replicate). And of course, tackling climate change through some Green Growth fantasy often employs all the same logics of growth and efficiency and all-gas-no-breaks that got us here in the first place. In short:

Our very attempts to think beyond our limitations reproduce those limitations.

Instead of coming up with new frameworks for managing unthinkability, we might need to examine how we can actively disrupt our existing frameworks without replacing them. Donna Haraway told us that much almost 40 years ago:9 Once we give up aiming for some allegedly representative or meta point of view, our partial, framed, and myopic perspectives can actually become a resource. They are manyfold starting points that can only make sense together – aware of their own limitations and actively striving to converse with others.

The Haitian revolutionaries didn't succeed by imagining a perfect post-colonial world and then back-casting it. They succeeded by acting in the gaps where colonial frameworks were already breaking down, using the very contradictions of the system against itself. They travelled on sight: cleverly, opportunistically, persistently and strategically seizing what was just about doable from here on out.10 Their actions made visible what the frame couldn't fully contain.

This in-between is where good futures can focus on. We can’t look beyond the frame, but we can see the frame itself – and maybe even its cracks.

Glitches̶̸̞̯̦̫̮̩̜̏̄̎̀ͥ̔̆͂̓̆ͥ̏ͯ̌ͯ̒̈ͤ̽̚͢͟͟ and Parasites

What would it look like if we started to focus on the edge of the present? What contradictions in our current systems are already causing breakdown? Where are our frameworks failing to contain reality? And what is emerging in these gaps and failures?

When we ask these questions we learn to recognise and work with the places where our ability to imagine fails us - where reality exceeds our frameworks even as we try to hold onto them. This is where the noise creeps in. This is where the parasites11 that might have been there all along come out of the dark: A shift in focus, a modulation in attention. A nuance that was a noise, a possibility, turning into a signal of the new.

Sherene Seikaly12 beautifully explores how across places marked by permanent crisis – from refugee camps to informal settlements to disaster zones – people are developing forms of persistence that exceed both the frameworks of emergency and development. What happens, when three generations have grown up in a “temporary” camp? When informal economies become more reliable than formal ones? When people rebuild – knowing perfectly well, perpetual destruction is certain?

It’s in these moments where we see forms of life emerging that can't be captured by the old frame of crisis or of progress. These aren't temporary solutions waiting for normality to return, nor are they paths toward some imagined future. They're practices of repair, maintenance and subverting that transform the very distinction between the temporary and the permanent. Rather than simply fixing what's broken, they help us to explore what else might be possible within the cracks of the present.

They are glitches.13 And once we look for them they are everywhere: Migration slipping through the cracks of rigid citizenship categories. Legal systems faltering under problems that cross jurisdictions. Identities no longer conforming to binaries.

Glitches aren’t failures to resolve – they’re signs that our frameworks can no longer contain the complexity of the world. They are not weak signals14 for a future that’s to come, but irritations of a present that is already here. Weak signals, though faint, are already signals: oriented toward meaning and significance they invite us to interpret and extrapolate, to fit them into existing frameworks, and to imagine what might come next. Glitches, on the other hand, resist interpretation. They exist somewhere between signal and noise, as nuisances: irritations that disrupt the very frameworks we use to make sense of the world. They are not yet meaningful but provocations to what we think is. While weak signals help us prepare for some kind of anticipated – or at least desired – future, glitches force us to confront the limits of our understanding of the present. They are about friction, rather than prediction, revealing cracks in the present where new possibilities – still unformed and unthinkable – begin to emerge.

What happens when we stay with the unresolved? What futures become possible when we stop demanding clarity?

The New is Beyond Prediction

Our limitations aren't just constraints - they're markers of where our frameworks break down, where glitches emerge, where parasites thrive. The silenced futures of the past never went away. They persist in the cracks of our present, not waiting to be discovered but actively remaking the world in ways we struggle to recognise.

If we move beyond understanding futures as destinations and treat them instead as tools to explore these breakdowns in our present, we might find a different kind of hope in face of despair. One that is already here. As Mark Fisher taught us:15

From a situation in which nothing can happen, suddenly anything is possible again.

Just because we don't see something doesn't mean it isn't there.

And just because we can't imagine something doesn't mean it won't happen.

“The New is beyond prediction.”16

And, as with Haiti, sometimes even beyond recognition.

This point is explored beautifully by Michel-Rolph Trouillot in Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (1995)

Frederick Douglass and W.E.B. Du Bois were among the first to emphasise the Haitian Revolution’s significance. Douglass, in his 1893 “Lecture on Haiti,” celebrated it as a symbol of Black resistance and freedom. Du Bois later linked it to global struggles against oppression in The Souls of Black Folk (1903).

“[N]ow more than likely that those born today will experience a +3ºC planet (at minimum and if we ignore tipping points). Without hyperbole, this is the basis for societal collapse.” – https://medium.com/neighbourhood-public-square/3%C2%BAc-neighbourhood-582903b050b2

With Elena Esposito’s essay Kommunikation mit Unverständlichen Maschinen (2024)

Lucius Burckhardt was one of many to do so, as early as in the 1970s, and this post heavily draws upon his beautiful writings on futures.

Explored, for instance, by authors like Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham (black futures), José Esteban Muñoz (queer futures), Ziauddin Sardar (decolonial / critical muslim futures), Saidiya Hartman (critical fabulation), Karen Barad, Donna Hathaway, Octavia Butler, and so many more…

Michel-Rolph Trouillot: ibid.

Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (2009)

Donna Haraway, Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. (1998) https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

Others have called this the ‘adjacent possible’. For instance Stuart Kauffman: https://www.edge.org/conversation/stuart_a_kauffman-the-adjacent-possible

Definitely for another post, but in short: Michel Serres’ absolutely brilliant concept of the Parasite (1980) examines how relationships are shaped by interruption, exchange, and dependency. A parasite isn’t merely a freeloader; it subtly disrupts the system it inhabits, whether by introducing noise, diverting resources, or altering interactions. Its existence often leads to new dynamics, connections, or forms of order, shedding some light on how systems evolve through interference, noise and transformation. 🪲

Sherene Seikaly, Nakba in the Age of Catastrophe (2023): https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/45037

See for instance: Shawn Bodden and Jen Ross: Speculating with Glitches: Keeping the Future Moving (2024): https://doi.org/10.56687/9781529244250-006 and on Glitches and Genders: Legacy Russell: Glitch Feminism (2020)

See for instance: https://www.sitra.fi/en/articles/what-is-a-weak-signal/

Quote from Mark Fisher ibid.

Quote by Ranulph Glanville in A (Cybernetic) Musing: Design and Cybernetics. (2009)

Brilliant read Simon!

This is such a massive, multithreaded and visual text!

I remember what resistance and anger the sentence "the future is already here, just unevenly distributed" aroused in me. And this sentence says so much about unreflective foresight or innovation management, in which it is enough to buy, take over or copy approaches, solutions, which is de facto looting! Mainly because there is no partnership in these talks, only a huge difference in power and resources (money).

And this formulation that some futures are "silenced" and yet are lingering under the surface and can take off and create new futures- I really felt it!

And I would love to see foresight as a tool/method to leveling the playing field, perspectives and reversing power structures!