Beyond the Binary

Draw a distinction – and cross it.

Climate action vs. economic collapse.

Freedom vs. collective responsibility.

Innovation vs. stability.

So often, our debates – political, organisational, even personal – endlessly cycle through these binaries. Back and forth – each side convinced they’re protecting a future the other would destroy.

But what if, in the most daunting challenges we face, choosing a side is exactly what’s holding us back from moving on?

Binaries aren’t inherently bad. They’re essential to how we make sense of reality. They help us navigate complexity, sharpen our priorities, and mobilise action. But this clarity always comes at a price: the unseen trade-offs, the night-sides,1 the unexplored possibilities that lie beyond our either-ors.

To move out of these loops, we might not want to pick a side, but to recognise the space in-between two sides as an interface: a space charged with friction, tension, and potential.

Interfaces aren’t always comfortable. They challenge us. They demand translation. But it’s precisely here – in the uneasy space in between the binary – that we discover pathways we couldn’t imagine from either position alone.

This is a piece about navigating those interfaces consciously, deliberately, and productively. I want to unpack the logics behind the binaries we live and work with.2 About how we move beyond – not by erasing them, but by crossing them.

Let’s move.

To draw a distinction

I’ll lend a few perspectives from a school of Systems Thinking that is not as prominent in my news feeds as it maybe should be: The perspectives that focus not so much on interrelations, connections, and links – but on boundaries.

Just as much as it is about relations, systems thinking is about boundaries.

Thinking in systems means to think in boundaries.

It’s the backside of any notion of holistic, interconnected, interwoven networks that often get associated with the overused tag line of “Systems Thinking”. It acknowledges that in order to make sense3 we are bound to draw a boundary, a distinction of what we mean / look at / prioritise – and all the rest.4 Only through its boundary a system genuinely becomes what it is. It marks the difference between a system and its environment. And with that boundaries are inherently paradoxical: they create interdependency precisely by drawing a line:

They are interfaces.

What follows is a framework for moving within and beyond binaries in five steps:5

① Affirmation → ② Objection → ③ Integration → ④ Negation → ⑤ Contextualisation.

This is not a linear path but a cycle, a tool for keeping in motion while acknowledging the gaps along the way.6

1. Affirmation

The One.

This is the not-yet differentiated starting point for our discussions, a point of interest that can serve as a topic, a theme, a value – sovereignty, freedom, solidarity. It serves as a place for mutual agreement, precisely because here, difference and nuance are not yet framed. It’s a sort of pre-distinction - crude but therefore powerful.

Most political claims work on this level: “We want growth!” – and they do work, because it remains open, at what cost this side can be had.

Innovation discourse all too often is found here, too: A rallying cry - „We need to innovate!“ - that initially unites before someone asks all the crucial questions of 'innovation for whom?' and 'at what cost?' - or even ‘what for?’

This unified starting point is compelling, but eventually needs differentiation.

Affirmation rallies us, but its power fades the moment we face complexity. Eventually, every simple idea encounters resistance. Objection reveals the night side of our binaries – the resistances and hidden costs we must confront.

So we move on.

2. Objection

The Other.

As we unpack our initial concept, we introduce difference and dissonance. For any concept we’re looking at we can distinguish (at least - but we’ll get there7) two sides.

We can map these two sides as two ends of a spectrum and we get exactly the type of zero-sum game that our collective discourse so often ends up in: growth vs sustainability, justice vs peace, democracy vs efficiency.

The climate debate often collapses into 'economy vs environment' thinking. We see this when pipeline protests are framed as 'jobs versus trees,' reducing complex realities to a zero-sum game that often limits what might be possible.

And – infinitely more abysmal – Gaza has become a site of relentless, deadly repetition of a binary between freedom and security. Each side justifies its position through the fear of the other. In the process, nuance is erased, history is flattened (literally), and the possibility of peace pushed ever further away.

This is the world of binaries: our positions make us choose and relate both sides in a mutually exclusive manner. Either A or B.

A common framing of these dichotomies – especially in the context of innovation and transformation work - is the temporalisation of the binary into a from and a to: From inequality to justice, from extraction to regeneration, from parts to systems.

To be sure: This second step is important. It helps us orient and often times prioritise where we want to go and what we want to avoid. But also, working within these dichotomies implies a trade off: We stay trapped in an either-or.

More precisely: posing a dichotomy is literally a power move. Binaries aren't neutral tools of thought – they reflect and reinforce power structures, norms, ideologies. Who gets to establish which distinctions matter? And what are the binaries that we go with without noticing?8

We can also call this a first order observation: we see one side, at the expense of the other, robbing ourselves of the option to see one within the other.

Objection clarifies, but it traps us in endless opposition. When we tire of binary battles, it’s tempting to just filter out the other. But to move on, we must open up and integrate: create spaces we haven’t yet imagined.

So we move on.

3. Integration

Both-And

Now it gets interesting. What if we reject the notion that one side is only realisable at the expense of the other? What if we move beyond the binary and shift toward a logic that genuinely is capable of being multivalent: holding two values at the same time - connected but not competing?

What emerges isn’t a compromise. It’s a field of positions and options within space for coordination, mediation, and integration. Thinking in this mode opens up genuinely new questions to ask. Questions that do not force us to pick a side. Rather, they force us to keep both sides in view when taking positions, making decisions that are deliberate and truly hybrid, both-and, constellations.

And this can be very productive:

In 1996, after centuries of colonialism, imperialism, and apartheid, South Africa country faced what seemed like an impossible choice: pursue justice through prosecuting human rights violators—or prioritise peace through reconciliation and forgiveness? Conventional wisdom insisted these were mutually exclusive paths.

Instead, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) refused this false dichotomy. It introduced a radically integrative idea: perpetrators could receive amnesty – but only if they fully disclosed their crimes. Justice was delivered through truth-telling and public accountability, rather than retribution. And victims weren’t simply asked to forgive, they were given a platform to share their stories and have their suffering acknowledged.

Justice and reconciliation weren’t opposed – they were interwoven.

At least, that was the plan.9Despite its serious limitations the TRC demonstrated something profound: When we move beyond seeing conflicts as simple either/or choices, new possibilities emerge. Even, and maybe because, this just allows for telling new stories.

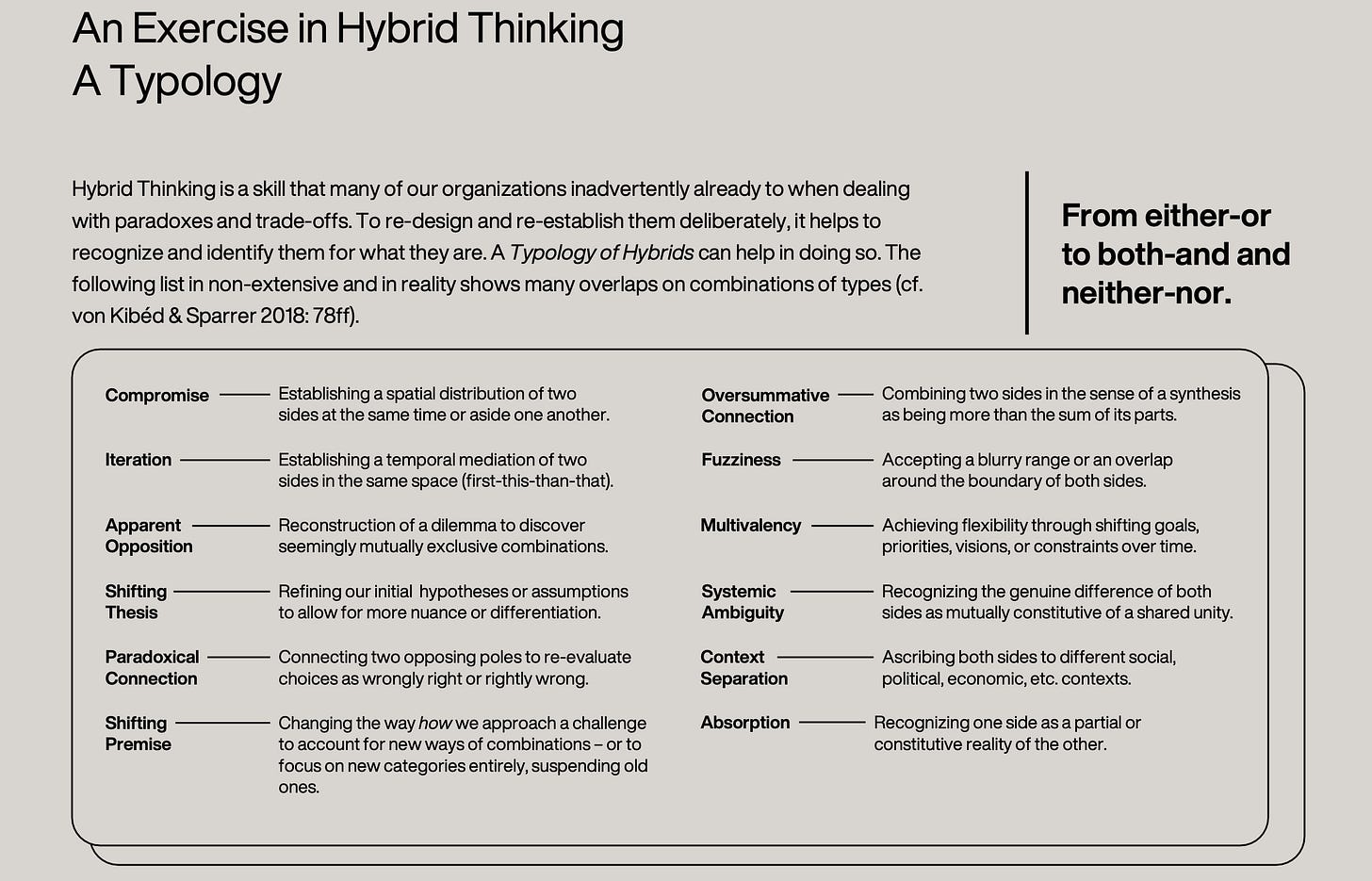

In a previous work we explored this form of Hybrid Thinking and drew on principles from systemic therapy10 to map a Typology of Hybrids – a (non-exclusive) classification of how we, our organisations and systems tend to deal with both-and scenarios:

We can call this view a second order observation: We reflect on the differences we drew before, and make them deliberate again. We observe our own observation – a tricky but essential skill.

But even integrated approaches have limits.

Integration doesn’t erase complexity – it actively embraces it. But even hybrids remain defined by the original binary, still caught within its gravitational pull. They miss the option for new differences, and remain integrated but confined. To truly move beyond, we need to enter the space of negation.

So we move on.

4. Negation

Neither-nor

What happens if we move beyond the either-or and even beyond the both-and of our binaries – toward the neither-nor?

We end up in an odd place.

Here, we deliberately leave the old dichotomies behind, but they never truly leave us. It is an explicit rejection of the old categories – a move away from the old, while not yet grasping the new. A liminal space, still defined by its past in the negative: post-capitalism, post-colonialism, post-modernity.

It’s the intentional negation of the binary of master and slave, with both lingering in the background. It’s the "I don’t see color" that points so heavily toward what it aims to move away from. In this space, the old binaries are neither affirmed nor entirely erased—they haunt us, even as we strive to transcend them.

Many of the more recent protest movements operate in this space. From Occupy Wall Street to Friday for Future to Wir sind mehr (recent anti-right protests in Germany), their power comes from a shared refusal. Of Wall Street’s greed, of political corruption, of lost futures and growing inequality and market logics. These movements create space, solidarity, and imagination by not filling in the blanks. They unite in opposition but struggle to stabilise. Without new structures, Occupy dissipated, and the forces it opposed reasserted themselves, often more aggressively.

The post-colonial condition marks a similar state. After colonial empires formally ended, many nations rejected the binaries of coloniser and colonised, of foreign rule and national identity. Yet what followed was not a clean break, but a haunted aftermath that was quickly vulnerable to capture: Neocolonial extraction, elite continuity, imported institutions—echoes of the binary lingered. The rejection of colonial rule didn’t automatically produce liberation. It produced a liminal space: not the old, not yet the new – always at the risk of slipping back to old binaries in disguise.

Negation frees us from old frames, but it leaves us suspended in limbo – a space defined only by what it is not. Eventually, we need new stability. Contextualisation provides this next evolution. From here we can re-stabilise.

Find a new distinction.

And move again.

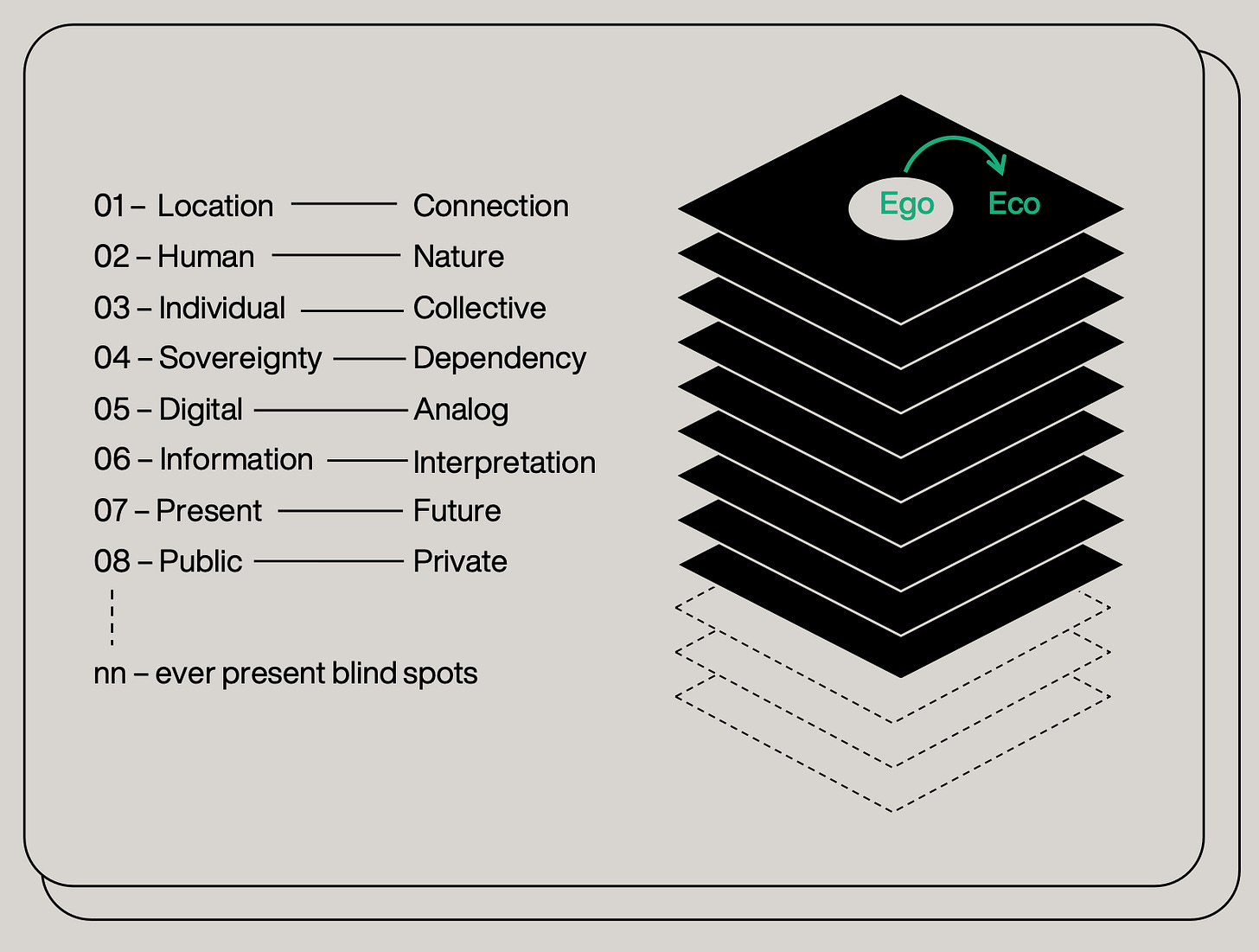

5. Contextualisation

Eventually every system will fall into a new form of stability, re-finding its focus, its core difference, its boundary again. We have now moved beyond the negation of the neither-nor into the genuinely new – a phase shift, an evolutionary step, a new type of sense-making that is no longer defined by the old, but layered on top of it. This moves us into a territory where we can account for the multi-layeredness of our world.

How can this look like in practice?

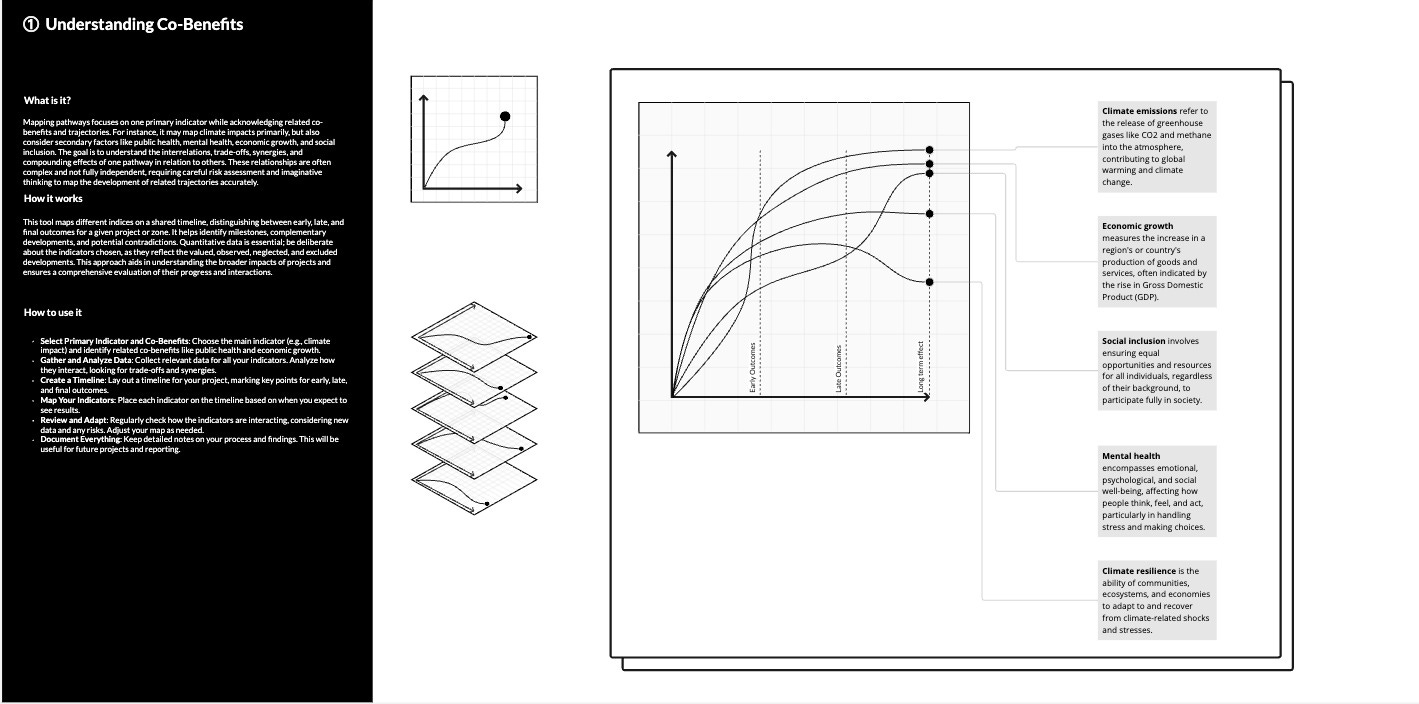

In my work with the EU Mission for Climate-Neutral Cities we try(!) to implement this type of multi-contextuality: While climate action began with simple 'reduce emissions' tunnel vision (affirmation) and quickly encountered 'economy versus environment' opposition (objection), the current approach tries to move beyond these limitations.

A single

interventionintersection like urban mobility redesign delivers measurable co-benefits across public health (reduced pollution), social equity (affordable transportation), economic opportunity (local business access), and mental wellbeing (green spaces). The Mission's “Climate City Contracts” require these co-benefits by design - ideally providing a space to work across traditional silos and recognise that meaningful climate action isn't a single-track goal but inherently operates at the intersection of many contextual, and often nested binaries.

From intervention to intersection

In a world of contexts, there is no way for any one actor – be it a planner, a city, or a government – to account for the many contexts they are acting in. Here, we are forced to think and act in constellations ourselves: in networks of mutual and collective contextualisation, of pointing out each others blindspots (the contexts we didn’t know we didn’t see), of taking parts of this complexity and leaving other parts to others.

This is very close to notions of intersectionality, the simultaneousness of difference and the possibility of many things being true at the same time. It also makes our understanding of an intervention or position very interesting - which now becomes a literal intersection, a specific constellation of multiple positions across a system of differences.

There’s no such thing as a single-issue struggle,

because we don’t live single-issue lives. – Audre Lorde

Designing such multi-contextual intersections is a genuinely social exercise, its genuinely endless (there is always another context) - but it can provide a more explicit frame work, a mental model, to hold difference in a way that remains productive and actionable while enabling us to account for the many worlds we live in.

The goal of this type of thinking is not to erase boundaries – they're essential for making sense of the world. Instead, it's to make our binaries more intelligent, more permeable, more alive. To treat them as the interfaces they are and to collectively move beyond the limiting loops we keep finding ourselves in.

South Africa's TRC wasn't perfect, but it demonstrated how moving beyond our binaries can be truly inspiring. By refusing the either-or of justice vs peace, Tutu, Mandela and many other charted a new path – imperfect, contested, but genuinely powerful.

Today's challenges demand similar courage. To move beyond our comfortable binaries and recognise them as interfaces: places of friction, possibility, and perpetual movement. Every meaningful change, every genuine innovation, arises at the interface—where differences meet, transform, and evolve.

Draw a distinction – and cross it.

As Achille Mbembe claims: the colony is the night-side of democracy.

Noting here that living beyond the binary has been a long standing experience for many communities that tend to fall through the cracks – and has been the subject of mixed race studies’ to queer culture and epistemology for centuries

In a very literal way: Drawing distinctions is how we make the world – which led many systems thinkers to become constructivists, from Gregory Bateson (and his focus on: “differences that makes a difference”) to Heinz von Foerster (and his work on second-order cybernetics).

The invitation to draw a distinction and to cross it is a taken from the first chapter of George-Spencer Brown’s Laws of Form (1969).

Building on the five steps of a tetralemma as translated into the notion of difference and transformation in Varga von Kibéd, Matthias, and Insa Sparrer. 2018. Ganz im Gegenteil: Tetralemmaarbeit und andere Grundformen systemischer Strukturaufstellungen. Zehnte Auflage. Heidelberg: Carl-Auer-Systeme Verlag.

And also on its translation into urban sociology in Baecker, Dirk. 2017. “Die Stadt Im Tetralemma. Fünf Positionen.” Pp. 224–35 in Explorations in Urban Practice, edited by K. Aßmann, M. Bader, F. Shipwright, and R. Talevi. Barcelona: dpr-barcelona.

Initial conceptual ground work for the following thoughts was done with my colleague Veit Vogel at the Hybrid City Lab.

🪲

Of course, Germans came up with an incredibly fitting word for the implicit (and therefore indisputable) exertion of power: Sachzwang - removing all responsibility behind a seemingly objective necessity (literally: coercion!) of the ‘thing’ at hand.

In reality, the TRC was far from perfect – from the get-go it had to face the accusation of re-producing the very impunity it aimed to overcome, of not addressing persisting underlying, economic and structural injustices, and of effectively achieving neither justice nor peace. Today, almost 30 years later, the long-term effects are sobering, to say the least, with SA being a deeply racially divided country still.

Varga von Kibéd and Sparrer, ibid.

Very good examples and illustrations. I am thinking - what happens if we talk about paradigms? Two different paradigms cannot co-exist, we either have one or the other. Or how do you see it?

Nature invented the cell membrane, to do just this. To form a boundary, an interface, and a potential across it. Then nested these boundaries, permeable to different signals.